OC 34/161-175 - Heinrich Schenker: Analysis of Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60, movements 1-3 (OC 34/161-175)

Editorial Note

Context: Writing of this analysis is recorded

twice in Schenker’s diary: October 11, 1913 “For the Little

Library, Brahms’s Piano Quartet in C minor”, and four days later

“Brahms Piano Quartet, Scherzo, dictated in sketch form (for the Little Library)”. This activity inter-related directly

with his teaching, as can be witnessed in his second lessonbook in 1913 and 1914;

for in teaching music repertory, Schenker often required pupils to make their own

analyses and read them out in the lesson for his correction.

Schenker

taught not only the solo piano repertory but also that of chamber music with piano.

On April 28, 1913, his long-time pupil Sofie Deutsch’s lesson notes read: “new:

Brahms Piano Quartet in C minor, first movement, form.” This was followed on October

6 with “Brahms Quartet in C minor, form in the first movement taken up anew and much

more intensively worked through (for more detail, see Little

Library!).” Mrs. Deutsch, who played chamber music with her friends,

worked on Op. 60 with Schenker on all four movements until February 5, 1914. Two

other pupils, Robert Brünauer and Hans Weisse, did so in October–December 1913.

Entries in the lessonbook that relate to or parallel remarks in this analysis have

been footnoted here in English translation.

This analysis follows that of

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1912) and the

Erläuterungsausgabe of Piano Sonata Op. 109

(1913), and precedes that of Op. 110, for which in October 1913 he was doing the

preparatory work. Pressure of work on the latter project probably contributed to his

abandoning of the Op. 60 analysis; nevertheless, it has some interest in charting

changes in his analytical approach in what is an important period in the development

of Schenker’s theoretical ideas.

Document description: This analysis is written on

fourteen sheets of paper (OC 34/161–174), laid out mainly in two columns, with

measure numbers in the left and analytical commentary in the right columns. (This

edition presents them in regular paragraphs, the contents of the left column being

in bold type.) It is written in the hand of Schenker’s future wife Jeanette

Kornfeld, by dictation or a mixture of fair copy and dictation. Subsequently,

Schenker worked over her copy, deleting some material, altering wordings, entering

new text interlinearly, and inserting music examples into spaces left by Jeanette.

Additionally, he added a graph on the reverse of p. 2 and a page of jottings with

music notation on p. 15 (OC 34/175). Not all the spaces left for music examples were

filled, and no analysis of the fourth movement seems to have been drafted. It was

written specifically for his series of booklets on individual works, entitled

Kleine

Bibliothek

(Little

Library) – a plan not realized in that form.

Measure numbers: Schenker’s measure-number

references are frequently followed by “ff”, which literally equates to “and the

following two measures.” However, many of these cases clearly imply more than two.

In the English translation, the editor has tried in such cases to provide more

specific references. Thus, for example “T. 35ff” in the second movement has been

translated “mm. 35[–43].” Where on the other hand “ff” denotes precisely the

following two measures, it has been rendered without brackets, thus “T. 27ff” in the

first movement as “mm. 27–29.” Where doubt exists, “ff” has been retained.

Music examples: The analysis includes eight music

examples, all in Heinrich’s hand, for seven of which Jeanette has left space blank,

the other being written on the verso of p. 2. In a

further seven instances Jeanette left space, in each case preceded by a colon, and

usually by “wie folgt” (”as follows”), but in these cases Heinrich did not enter the

item. It has, however, been possible to retrieve three of those seven from the set

of jottings in Heinrich’s hand on p. 15.

|

[in left

margin:]

⇧

Kl. Bibl.

†

Brahms Clavier Quartett Cmoll op. 60

⇧ 1. Ged. Vorders. u. Nachs. Daran schließt sich die

Modulationsgedanke an, mit dem Kopf noch in Cmoll, dann aber nach Es modulierend. 2. Ged. in Es mit einer bei

Brahms ungewöhnlichen Konstruktion: 5-malige Wiederholung, wobei man am besten

dem Gegensatz der Achtel- u. Triolenbegleitung gruppiren möchte: 2 : 3

Wiederholungen, in welchem Sinne dann die ersten beiden gleichsam den

Vordersatz, die letzten 3 den Nachsatz bilden. 3. Ged. T. 110–121 kommt auf den

1. Ged. zurück, der mit dem Motiv aus T. 38 kontrapunktirt wird. Durchführung T.

122–197; Reprise T. 198–Schluß!

1

T. 5 hat im Grunde zur Nachfolge T. 8–9; in den T. 6–7 wird der Ton c gewissermaßen zerdehnt, daher das �� ��. T. 9 Bei der Dominante fehlt die Terz h. T. 17ff Quintfälle: b – es – as – des – ges – c – f; die Melodie eine fallende Sekundreihe in Vergrößerung. T. 21 Dominante, wobei von der Quint chromatisch zur Terz gefallen wird, aber auch die Baß eine der Stimmführung entsprechende Bewegung von g, dem Grundton, wieder zur g zurück über ges–f u. zurück fis–g macht. eine groß auskomponirte Retardation des Sekund-Motivs. ⇧ ? T. 27ff In die Dominanten Harmonie spielen Br. Violine drastisch u. mit Absicht – man beachte p marcato – den unharmonischen u. undiatonischen Ton: e hinein; 2 es klingt beinahe wie Absicht u. Bosheit oder mindestens, wie wenn – um es ganz populär zu sagen – uns jemand an der Nase kitzeln würde, aber schon in T. 30 wird die Bedeutung des Tones dahin klargestellt, daß er als freier Vorhalt zur Sept der Harmonie gebraucht wird. Die Beziehung zur Sept drückt der legato-Bogen beim Klavier aus u. auf dynamischem Gebiete parallel die Wirkung anstrebend das �� -Zeichen: also, das fremde e wird von hier aus nachträglich rehabilitirt. T. 32 Nachsatz; Motiv im staccatto, Orgelpunkt auf c (siehe Vcl.) 3

{2}

Motiv T. 34 Figurirung des T. 5,

somit T. 38 Motiv bei Vcl. u. Br. Verkleinerung des Motivs beim Klavier T. 37.

T. 42ff Motiv beim Klavier abwechselnd bei der

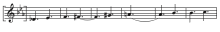

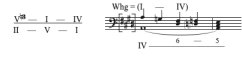

r. u. l. Hand; Sechzehntel-Kontrapunkt neu: ⇧ freilich T. 45 Eigentlicher Sitz der Modulation Cm nach Gm. T. 49 Modulation nach Esdur/moll; interessant beim 16tel Kontrapunkt die allmälige Verringung des Quartintervalles, das zum 1. mal in T. 44 zwischen dem letzten 16tel des 2. u. dem 1. des 3. Viertels sich öffnet. Im T. 48 wird aus der Quart eine Terz, T. 49 ein Sekundschritt: b – a.

T. 50 Das Brio des 16tel sich zum legato gelegt, nun

darf es im legato auch tranquillo werden.

4

[cue sign to

verso]

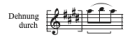

T. 72+73 sind im Grunde so zu sehen: [left blank] T. 74 Oktaven zwischen Sopran u. Baß, nicht nur wegen der Stufen, sondern auch wegen des dazwischentretenden Quartschrittes gut. T. 77 Dominante schließt die 8-taktige Tonreihe, so daß die nachfolgende Wiederholung zunächst als Nachsatz gehört wird. T. 78ff Variation der Melodie bei der Violine, wieder zur Dominante in T. 85. Man beachte die Verschiedenheit der Baßführung in T. 78–81 gegenüber der die T. 70–73. T. 86 Triolen-Begleitung Vl. u. Br.; Vcl. figurirt die Tonreihe des T. 70, worauf das Klavier im Thema fortfährt. T. 88 Beim Vcl. Verschleierung des Sachverhaltes durch Wiederholung des Motivs aus T. 86; man neigt infolgedessen in T. 86 die Bedeutung der Figur zu verkennen. Gerade eine solche Versch[l]eierung aber ist ech[t] symphonisch! {3} In T. 91 wieder Halbschluß, zum 3. male. T. 94 Wiederholung der T. 86ff, ebenso wie früher T. 77ff Wiederholung der T. 70ff gewesen. Mischung Esm. T. 100 Nicht mehr zur Dominante geht es, sondern eine kräftige Kadenz führt zur letzten 5. Wiederholung des Themas, die mit g, also eine Terz höher beginnt. T. 122 Beginn der Durchführung, 1. Motiv im Portamento; aber dieses Portamento erweist sich als der Uebergang vom legato zum staccatto im T. 142. T. 130 deutlich Esm. T. 138 vgl. T. 50 T. 142ff Plan: 5 Einem geschlossenen Bildchen in Hd, T. 142–151, bezw. 152 tritt eine modulatorisch suchende Partie von T. 154–163 gegenüber; nun wieder, aber in Gd, ein geschlossenes Bildchen, T. 164–174, dem wieder suchend u. modulierend eine Partie von T. 176 bis Ende der Durchführung gegenüber tritt; vgl. IX. Sinf. 6 T. 152–153 Ueberleitung vom geschlossenen Bild zum Gegenbild. T. 154 Beim jeweilig 3. Viertel Vorausnahme der Harmonie des jeweilig nachfolgenden 1. Viertels nach Art einer Synkope. In T. 156–159 beachte man als Grundtöne, (nicht als Stufen!) die Terz-Schritte d – b – dis – h. T. 161 Hemiolenartige Verdichtung; Harmonie: [music example probably intended but not entered] T. 176 Nach der Durchführung des Motivs des 1. Themas folgt hier eine des 2. Themas auf dem Orgelpunkt G u. kanonisch ausgeführt; die imitirende Stimme setzt zuerst im Abstand von 3 Vierteln, also eines ganzen Taktes ein, siehe T. 177–178, in T. 185 setzt, sie bereits nach 2 Vierteln ein, während sie endlich in T. 191 bereits nach einem Viertel einsetzt; hier tritt noch eine {4} 2. Stimme, siehe Klavier, imitierend ein. Harmonien!

Reprise

T. 236 2. Ged. in Gd statt in Cd, ungeheure Verbreiterung der Gdur Tonart: hier im Gegensatz zum 1. Teil 6x8 statt 5x8. 7 Die gewissermaßen überzähligen 8 Takte sind die T. 244–251; sie dienen nicht so sehr als wirkliche Wiederholung, sondern als Erzeugungsstätte des Baßmotivs der T. 252ff. Man beachte folgende, durch die Harmonien begründete Veränderungen des Intervalls: [music example, not entered] Ist so auch diese 8-taktige Gruppe mehr als Ueberleitungsgruppe erkannt worden, so müssen dann erst die Takte T. 252–259 als die wahre 1. Wiederholung gelten; treu dem Thema in den ersten vier Takten wird sie freier in den nachfolgenden 4 Takten, nur daß sie den Zug zur Dominante beibehält. Diese Wiederholungen nun werden – u. dieses macht die wirkliche Verbreiterung aus – noch einmal in Moll, kraft der Mischung, gebracht. T. 254 Scheinbar offene Quinten; in Wahrheit ein zufälliges Zusammentreffen zwischen der Nebennote des Basses cis u. dem Durchgang g des Soprans; man braucht also nur die Nebennote im Baß zu streichen, um sich zu überzeugen, daß keine Quinten-Fortschreitung vorliegt! {5} T. 260–269 Dehnung zu 10 Takten; nun erst die Triolenbegleitung, vgl. im 1. Teil T. 86, die den Nachsatz anzeigt. Dieser enthält wieder 2 Wiederholungen: die zweite T. 278 muß nun von T. 282 die Modulation nach der eigentlichen Tonart Cd bringen. Beethoven pflegte in solchen Fällen, d.h. wo er gleichsam unfreiwillig auf ein falsches Geleise geriet – s.z. B. Sonate Esd, op. 7, Rondo ,: Esd – Ed – Esd; Sonate op. 110, 1. S.: Asd – Desd – Cism – Ed – Asd 8 – schon früher in die Hauptonart einzulenken, mit einer Gebärde gleichsam, als würde er für die Entgleisung um Entschuldigung bitten u. als würde er sagen wollen, daß er sich gerade noch rechtzeitig erinnere, welchen Weg er eigentlich zu gehen habe. Hier bei Brahms steht die Sache etwas schlimmer: so richtig das beiläufige Hineinrutschen nach Gd als beiläufig dargestellt wird, so wenig richtig ist es, daß er Gd so lange ausführlich behält, so daß es für ihn zu spät wird um zu sagen: pardon, ich bin auf falschem Wege. Wäre es doch auch grottesk, wenn jemand, der an einem Tisch sitzt, an den er nicht gehört, dieses erst bemerken wollte, nachdem er die volle Mahlzeit genossen. Die Modulation bei Brahms ist daher ein notwendiges Uebel; sie klingt auch motivisch verlegen u. unwahr. Es ist sonst nicht Brahms Art, ohne weitere Uebergänge von Motiven, wie die in T. 279– 200 [recte 280] , zu solchen zu gelangen, die T. 282–283 zeigen. Aber freilich, er wollte zwei Fliegen mit einem Schlage treffen: die Figur des T. 283 soll nämlich noch außerdem den Vorfahren der Triolenfigur in T. 289ff vorstellen. Die Figur bleibt banal. Der Accord in T. 287 ist alterirt: Terz-Quart-Accord u. wird hier in der Bedeutung von V in C u. nicht II in Fm, benützt. {6} Bei T. 288 Schlußgedanke. Diesmal lastet auf ihm anders als im 1. Teil, die Verpflichtung die Haupttonart Cd nach der vorausgegangenen breiten Darstellung des Gd zur nachdrücklichen Selbstbehauptung u. zum Triumphe zu führen. Die Aufriß der

T. 288–300 lautet wie folgt: [diagram or music

example, not entered]

T. 30 50–30 83 bleibt. Die Kadenz selbst, T. 300–303, beschreitet den usuellen Stufengang: [diagram or music example, not entered] Die große Aktualität u. die intensive Durcharbeitung des Sekundmotivs läßt es uns zunächst gar nicht merken, daß der Kontrapunkt, wie ihn der 3. Gedanke im 1. Teil bei der Vl., später Vcl., s. T. 110–111, bezw. T. 114–115 bringt, entfallen ist. Dieser Kontrapunkt wird nun eben in T. 304–312 nachträglich u. zu einem selbstständigen Gebilde verarbeitet. So wurde der Schlußgedanke des 1. Teiles zuerst {7} in bezug auf das Hauptmotiv u. sodann in bezug auf dessen Kontrapunkt in 2 Teilen ausgeführt. Erst hier die Haupttonart Cm statt Cd. Das aus dem Kontrapunktmotiv gewonnene Bildchen zählt nur 4 Takte u. legt in sich wieder einen Kadenzweg zurück, so daß wir den Schluß in T. 307 bereits als den 2. Schluß bezeichnen. T. 308 bringt dasselbe Motiv in Triolen-Variation beim Klavier. In T. 312 wieder Schluß, somit bereits der dritte.

T. 313 Eigentlich mit diesem Takt Beginn der

Coda, wodurch der Parallelismus der Anfangskonstruktion T. 1–2, sodann zum

Beginn der Reprise, T. 198, gegeben ist. Letzte Darstellung des Hauptthemas bei

den Bässen, Klavier u. Vcl.; die Ueberwindung alles Staccattomäßigen –

schmerzliches legato; der Kontrapunkt steht über dem Thema, wie beim

Schlußgedanken, wodurch der Coda wieder der Schlußgedanken-Charakter aufgeprägt

bleibt.

{8}

II. Satz: Scherzo

Scherzo mit ; Scherzo bis T. 71 – weder durch Vorzeichen noch durch Doppelstriche oder Titel gesondert von T[.] 72–114, hierauf Ueberleitung von T. 115–154, von T. 155 Wiederholung des Scherzo. Einleitung[:]

T. 1–4 kündigt die Motive an u. sofort auch

schon mit allen Elementen der Mannigfaltigkeit, so T. 5ff mit Auftakt, sehen wir die Elemente in vollster Tätigkeit: zunächst die 3-Tönigkeit u. die Bewegung aufwärts in 10

T.

56–16. T. 9 auf der VII Stufe die Mischung u. Einführung der Terz „des“, die aber

im Interesse der Diatonie doch wieder weggebracht wird. Als Konsequenz des

„des“, das von der Diatonie zu weit wegführt, sind „as“ in T. 11, „des“ in T.

12, wo die Enharmonie einsetzt (des=cis), u. ein Quintschritt vollzogen wird:

cis–fis, T. 13.

11

Die Enharmonie mußte also zuhilfe genommen werden um den starken Bruch gegenüber

der Diatonie

⇧ u. den

Mangel an Ton-[?Kultus]

irgendwie gut zu machen. Die Dauer dieses Grundtones beträgt, ebenso wie die der

beiden vorhergehenden, 2 Takte. Nun geht es mit je 2 Schlägen in T. 15 u. 16 in

Quinten: d – g – es – as.

12

Durch die Enharmonie u. die letzgenannten

Grundtöne ist der Einschlag der VII

ę3 Stufe überwunden

⇧ u. zugleich die Mod. vollzogen u.

wir befinden uns mindestens von d ab in der

⇧ neuen Diatonie

⇧ gm.

13

Den Fortgang der Sekund in der Melodie, wie er gerade

durch diesen Stufengang ermöglicht wurde, mag folgendes Bild

veranschaulichen: T. 17 erscheint die I ⇧ Ě3 von ihrer VII. präludiert, in T. 18 die VII, ebenfalls von ihrer VII. präludiert (als ihrer Nebennotenharmonie) u. erst in den ⇧ in den T. 19–20 ⇧ wird die Modulation durch ⇧ der ⇧ Terz-Schritte: f–as–c zu d–fis–a 14 vollzogen, ⇧ worauf die letzte Kadenz einsetzt[.] ⇧ Freilich wurde die Eindruck dieser Modulation dadurch gefördert, daß die vorausgegangene Stufengang sich in Grundtönen bewegte, die eine Modulation sogar schon früher nahelegen konnten. [square-bracketed (by JK):] Für die beiden Annahmen liegen übrigens gleich triftiger Gründe vor. T. 12, desgleichen T. 14–15 weisen Antizipationen beim letzten Achtel auf, bei welcher Gelegenheit der Baß einen Oktavsprung macht[.] Diese Antizipation samt Oktavsprung ist Vorbild der Baßführ- {9} -ung von T. 17 an, die sich zu einem noch dichteren Rhythmus steigert. Bei dem Sopran in den T. 17ff beachte man die wohltuende Wirkung, die in T. 19 die Umstellung des Terzintervalles der Melodie es–cis hervorbringt, das in die 2. Hälfte des Taktes gerät, während es bis dahin die 1. Hälfte des Taktes occupiert hatte. In

T. 21 wird aus dem Oktavsprung des l.H. ein

Quart-Intervall, das sich sofort mit

explosiver Wirkung auf imitierendem Wege 4mal fortsetzt. Auch dieses Motiv

erhält, wie wir später sehen werden, Bedeutung. T. 23–33 eine Art Bestätigung, die die neue Tonart durch ein kleines selbständiges Bildchen erhält. Ein Brahms’sches Spezifikum, auf dem Plateau der Dominanten-Tonarten ähnliche kleine Gebilde aufzustellen, ohne damit aber etwa die Absicht zu verbinden, ein Mittelstück der 3-teiligen Liedform zu geben. Nicht unoriginell ist die rhythmische Konstruktion des kleinen Sätzchens: T. 27 Mischung, T. 30 Abkürzung zu blos 3 Takten, die Rhythmik erinnert an die Schubertsche. 16

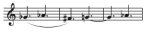

T. 35ff Die Wiederholung betreibt die

Aufwärtsrichtung bis T. 43; von der VII. Stufe wendet sich hier aber der Autor

zur III., die er in Moll setzt: e–ges–b. Dieses ges, das, ebenso wie in T. 9,

doch früher oder später fallen mußte, gibt hier Veranlassung zur Enharmonie: ges

= fis u. bei diesen, der enharmonischen {10} Umwechslung angepassten

Grundtönen h – e – c – f erobert er wieder die Diatonie. Die Sekundfortgang

lautet hier: So kann er endlich bei T. 44 die Abwärtsrichtung in Angriff nehmen u. die Kadenz in Scene setzten: in T. 45 der 1. Anlauf zur Dominante über die erniedrigte II.; in T. 46, 47 der 2. Anlauf über IV–V; nach diesen 2 kurzen Anläufen der dritte umständlichere, der bereits zum Schluß führt. In den T. 48–49 die Stufen as – es – Bb – f (man beachte, wie der Ausgangspunkt um eine Terz höher fällt: des in T. 44, f in T. 46, as in T. 48, welche Punkte in sich ⇧ chr. Sinnung schon die ę III. Stufe der Tonart ergeben). Nun in T. 50–53 die ę II. Stufe breit exponiert. In T. 54–61 das Kadenz-Motiv selbst. Es klingt wie eine Erweiterung des Motivs in T. 17ff (statt der Quart dort ⇧ der Quint hier). In T. 55 die I. Stufe, in T. 56 die IV, in T. 57 die VII. in T. 58 Durchgang zur V. in T. 59; vergleiche denselben Stufengang in den T. 17–20. Ueber 2 Chromen, die auf die Nebennoten-Harmonie der IV. hinweisen zur IV. in T. 60–61 u. in T. 61 die Dominante, in T. 62 die Tonika als Schluß. Auf die Tonika die Nebennoten-Harmonie der ę II.; das Motiv ist das Quartmotiv aus T. 21. Interessant ist, daß eben dieses Cadenzerscheinung zunächst in 3 Schlägen erledigt wird, während sie bei der sofortigen Wiederholung zu 4 Schlägen erweitert wird! 17 Dieses geschieht durch die Beteiligung der Bratsche, die unter die Harmonie der II. Stufe eine um eine Terz tieferliegenden Grundton: h setzt. 18 Die Tonika hat die Dur-Terz, vgl. Band I. 19

{11}

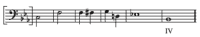

Trio. in Fdur,

20

fängt somit mit der Dominante an, der

Stufengang erweist, daß Brahms darauf bedacht war; den V.S. mit der IV.

abzuschließen, um den Anschluß: IV–V zu Beginn des Nachsatzes erreichen zu

können. Eine seltene Konstruktion, vgl. des Meisters IV.

Sinfonie, Scherzo, II. Ged. Der Stufengang ist im Vordersatz

folgender: Man beachte in T. 82–83 u. in den parallelen T. 84–85 21 die Konstruktion des Achtel-Kontrapunktes: eben der Umstand, daß in T. 83, bezw. T. 85, schon das 2. Achtel, u. nicht wie in T. 82 bezw. T. 84 das 4. de nr Ton „d“ bezw. „b“ ist, ist dafür maßgebend, einen Wechsel der Harmonie anzunehmen. Das Bild von T. 84 stellt sich wie folgt: [diagram or music example, not entered]

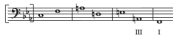

Nachsatz: Daraus ergibt sich ein Schluß zur Tonika von der III. Stufe fallend: III–I. Die nicht in Verwendung gebrachte Dominante klingt aber über der Tonika in den

T. 107–114 fort, zugleich die Rückleitung

vorbereitend.

{12}

III. Satz

A1: Vordersatz: T. 1–8, Nachsatz: T. 9–16. T. 1. Stufen: I–IV5/Ě3, nicht aber II6/5, also fis blos Durchgang. T. 4 Vorhalt 7 6, gis–fis T. 5 Beim 3. Viertel Wechselnote e. 22 T. 11 Orgelpunkt auf I Ě7, also I – IV – ě IV – I [centrally under this expression is "I" linked by horizontal curly bracket.] T. 17 Wiederholung, nicht Nachsatz, die aber nicht mit der Tonika, sondern mit der Dominante, in T. 26 schließt nach Art eines V.S., um zum 2. Teilgedanken 23 besser hierüberführen zu können.

T. 19ff

T. 20–22 Die IV. Stufe mit ihrer

Unterdominante, die sich wie folgt aus dem Durchgang erklärt: Beim 3. u. 4. Viertel des T. 22

ě

IV. Stufe. In T. 20 wird zweimal gesetzt, ein

Element des sofort im T. 21 auftretenden Teilmotivs vgl. T. 5. Die Duplizität in

T. 20 ist auch Ursache der Duplizität in T. 21.

T. 23ff Eintritt der V. Stufe u. Kadenz. Das

Kadenz-Motiv, dasselbe wie in T. 7, passiert in T. 24 das Cello, in T. 25 das

Klavier (l.H.) {13} u. kehrt in T. 26 wieder zur Violin

zurück. T. 27ff II. Teilgedanke, der auch die Modulation bringen soll, wird eröffnet mit der Tonika in Ed. T. 30 findet die Modulation Umdeutung der VI. aus Ed in eine II. aus Hd statt. In T. 31 bereits die V. von Hd. In T. 32 beim Klavier offene Quinten 7/3 6/2 5/1. T. 35 B1 in Hd; aus 2 verschiedenen Charakteren zusammengestellt; man siehe den Typus in T. 35–36 u. in T. 37ff. Der 1. Teil des Ged. zählt 4 Takte, T. 35–38 u. wendet sich über die VI. u. II. Stufe in T. 38 zur Dominante, mit der der II. Teil eröffnet wird, um über die II ě3 in T. 43 auch wieder mit der Dominante in T. 45 zu schließen. T. 46ff Nachsatz des II. Ged. mit Dehnungen, siehe T. 47. Statt der T. 37–38 hier im Nachsatz eine Wiederholung der T. 35–36 = 46–48. Bei T. 52 die Situation wie bei T. 39. T. 56 Zur Kadenz; die Anlage derselben weist zunächst auf eine Kadenz in Hd hin, während das Klavier eine nunmehr 2. Wiederholung des Gedankens bringt, aber der Stufengang in den T. 59–61 zeigt eine Rückmodulation nach Ed: in T. 59: VI–II, in T. 60: VII–III, in T. 61: I., die in eine V. in Ed umgedeutet wird, so daß daselbst in der 2. Hälfte des Taktes eine Tonika aus Ed erklingt. T. 62ff Ueberleitung zu A2; Motiv aus dem 2. Ged. bis T. 69; in T. 70 klingt beim Cello das Motiv des T. 1 als 1. Ankündigung des A2; die zweite erfolgt in T. 75. Die Beziehung, in der die Tonarten der Ankündigungen stehen, ist besonders bemerkenswert : Cdur/moll – Asdur/moll – Edur/moll in T. 78. Erwägt man, daß vor Cd in T. 70 bis dahin bereits Ed herrschte, so weiß man in dem Ablauf der 3 in Entfernung von großen Terzen liegenden Tonarten: E – C – As(Gis) – E die Ursache für den Wohlklang der Ed-Tonart bei Beginn von A2 {14} anzuegeben. T. 78 A2; Melodie beim Klavier. Die Veränderungen liegen klar zu Tage. T. 111 B2 reduziert.

T. 117 zur Unterdominante, Dominanten Schluß in

T. 118, 119–120 plagale Schlüsse.

© Transcription Ian Bent, 2021 |

[in left

margin:]

⇧

Little

Library

†

: Brahms Piano

Quartet in C minor, Op. 60

⇧ First theme, antecedent and consequent. Contiguous

to that is the modulatory theme, at the outset still in C minor, but then

modulating to Eę. Second theme in Eę with

a construction uncommon in Brahms’s works: fivefold iteration, which might best

be grouped by the contrast between eighth note and triplet accompaniment: 2 + 3

iterations, the first two accordingly forming, as it were, the antecedent, the

latter three the consequent. Third theme, mm. 110–21, reinvokes the first theme,

which is set in counterpoint with the motive from m. 38. Development section mm.

122–97; recapitulation mm. 198–end!

1

m. 5 is in principle continued by mm. 8–9; in mm. 6–7 the note C is somewhat extended, hence the �� ��. m. 9 The third, BĚ, is absent from the dominant. mm. 17[-20] Succession of descending fifths: Bę – Eę – Aę – Dę – Gę – C – F; the melody an expanded succession of descending seconds. mm. 21[-27] Dominant, in which occurs a chromatic descent from the fifth to the third, and in addition the bass line describes a motion, in accordance with the voice-leading, from G, the bass note, back to G, passing through Gę to F and back again via Fě to G – an expansively composed-out retardation of the motive of a second. ⇧ ? mm. 27-29 Into the dominant harmony the viola and violin inject abruptly and with intent – NB the p marcato – the non-harmonic and non-diatonic tone E; 2 it sounds almost as if done deliberately and with malice, or at least as if – to put it in popular terms – someone were to tickle our nose, but already in m. 30 the significance of that tone is explained: it serves as a free [upward] suspension to the seventh of the harmony. Its relationship to the seventh is expressed by the legato slur in the piano part, and parallel with that in the dynamic sphere by the crescendo sign, which strives for the same effect at the dynamic level: thus, the foreign E is rehabilitated after the event. m. 32 Antecedent; motive [now played] staccato, [with] organ-point C (see cello). 3

{2}

Motive m. 34 Figuration from m. 5,

thus: m. 38 Motive in the cello and viola [is a] diminution of the motive in the piano at m. 37.

mm. 4

2 [recte

3]

[-49]

Motive in the piano

alternating between right and left hands; sixteenth-note counterpoint new:

⇧ thus m. 45 True site of the modulation from C minor toward G minor. m. 49 Modulation toward Eę major/minor; interesting in the sixteenth-note counterpoint [is] the gradual narrowing of the interval of a fourth, which opens up for the first time in m. 44, between the last sixteenth of the second quarter note beat and the first of the third. In m. 48 the fourth becomes a third, in m. 49 a second: Bę–A.

m. 50 The brightness of the sixteenth

note[s] settles down to a legato, now in legato it can also become tranquillo.

4

[cue sign to

verso]

mm. 72-73 In essence, they are: [left blank] m. 74 Parallel octaves between treble and bass are good, not only by virtue of the structural harmonies, but also by virtue of the intervening leap of a fourth. m. 77 The dominant closes the 8-measure melodic line, so that the succeeding iteration is now heard as a consequent. mm. 78[-85] Variation of the melody in the violin, [leading] again to the dominant in m. 85. Note the difference in the bass line in mm. 78–81 as against that of mm. 70–73. m. 86 Triplet accompaniment in violin and viola; cello creates a figure out of the note-pattern at m. 70, whereupon the piano carries the theme forward. m. 88 The repetition of the m. 86 motive in the cello causes a veiling of the situation; as a result, one is inclined not to recognize the significance of the figure in m. 86. But such a veiling is genuinely symphonic! {3} In m. 91 again a half-cadence, for the third time. m. 94 Reiteration of mm. 86[–93], just as earlier mm. 77 [recte 78] [–85] were a reiteration of mm. 70[–77]. Mixture Eę minor. m. 100 It no longer goes to the dominant; instead a powerful cadence leads to the fifth and final iteration of the theme, which begins with the note G, thus a third higher. m. 122 Beginning of the development section, motive 1 in portamento; but this portamento proves to be the transition from legato to the staccato in m. 142. m. 130 clearly Eę minor. mm. 138[-40] Cf. mm. 50[–52]. mm. 142[-97] Plan 5 : A closed unit in B major, mm. 142–151(152), is now confronted by a passage, mm. 154–163, which seeks to make a modulation; and then again, but now in G major, a closed unit, mm. 164–174, is confronted by a passage, mm. 176 to the end of the development section, which again seeks to make a modulation; cf. Ninth Symphony . 6 mm. 152–153 Transition from the closed unit to the contrasting section. m. 154 On the third quarter note beat of each measure, the anticipation of the harmony on the first quarter note beat of the following measure [creates] a sort of syncope. In mm. 156–59 NB as bass notes (not as structural harmonies!), the steps of a third: D – Bę – Dě – BĚ. m. 161 Hemiola-like compression; harmony: [ music example probably intended but not entered ] m. 176 After the development of the motive of the first theme, there follows at this point one of the second theme deployed canonically over the organ-point G; the imitative voice enters at first at three quarters’ distance, thus a whole measure apart, see mm. 177–78, then at m. 185 it enters earlier, at two quarters’ distance, while finally at m. 191 it enters still earlier, at one quarter’s distance; at this point there enters a {4} second voice, see the piano part, in imitation. Harmonies!

Recapitulation

m. 236 Second theme in G major instead of C major, massive expansion of the G major key: here, in contrast to the first section, 6 x 8 instead of 5 x 8. 7 The supernumerary eight measures are mm. 244–51; they serve not so much as a genuine iteration, but rather as the source of the bass motive at mm. 252[–66]. Note in what follows the harmonically-based alterations of the interval: [music example, not entered] If then this 8-measure group is also perceived more as a transitional group, then first the measures mm. 252–59 must count as the true first iteration; adhering faithfully to the theme in its first four measures, it [i.e. the group] becomes freer in the following four measures, except that it conserves the motion to the dominant. These iterations are now – and it is they that provide the real expansion – once again brought into the minor key by virtue of mixture. m. 254 What appear to be parallel fifths are in reality an accidental concurrence of the neighbor-note Cě in the bass and the passing tone G in the treble. Thus it is necessary only to excise the neighbor-note in the bass to be convinced that no fifth-progression exists! {5} mm. 260–69 Extension to ten measures; only now [comes] the triplet accompaniment (cf. m. 86 in the exposition), which heralds the consequent. The latter again comprises two iterations: the second, m. 278, must now from m. 282 bring the modulation round to the rightful key of C major. Much earlier, Beethoven in such cases – i.e. where he has strayed almost involuntarily on to a false path, as for example in the Eę major Sonata, Op. 7, Rondo: Eę major – E major – Eę major; Sonata Op. 110, first movement: Aę major – Dę major – Cě minor – E major –Aę major 8 – used to come back to the principal key with a gesture as if he were apologizing for the derailment and wanted to say that he had realized at the last possible moment which path he was actually supposed to take. Here, in Brahms’s music, the matter is somewhat more serious: however justified it may be to present a brief slip into G major as a passing phenomenon, it is less than justified for him to dwell elaborately and for so long in G major, such that it becomes too late for him to say: “Sorry, I’ve taken the wrong path.” It would be downright grotesque if someone who sits at a table to which he doesn’t belong fails to notice the fact until he has finished the meal. Brahms’s modulation is therefore a necessary evil; even motivically, it sounds embarrassed and inauthentic. It is not Brahms’s normal way to arrive at such transformations as are found in mm. 282–83 without further motivic transformation of the sort shown in mm. 279–80. But of course he wanted to kill two birds with one stone. The figure at m. 283 will in fact even prove to be the precursor of the triplet figure in mm. 289ff The figure remains banal. The chord in m. 287 is altered: [it is a] 4/3-chord, and is employed here in the sense of V of C, not II of F minor. {6} At m. 288 cslosing theme. This time, unlike in the exposition, it is charged with the obligation to carry the principal key, C major, after the preceding, expansive presentation of G major, through to emphatic self-reassertion and to triumph. The plan of

mm. 288–300 is as follows: [diagram or music

example, not entered]

mm. 30 50–30 83 The cadence itself (mm. 300–303) follows the conventional structural harmonic progression: [diagram or music example, not entered] The sheer amount of activity and the intensive working out of the second motive distracts us completely from noticing the absence of the counterpoint that the third theme presented in section I in the violin, later cello (mm. 110–11 and 114–15). This counterpoint now in mm. 304–12 [are] developed belatedly and as an independent unit. Thus the closing theme of section I was at first {7} set forth with reference to the principal motive, and subsequently with reference to its counterpoint, in two partitions. Only now here [is] the principal key C minor, instead of C major. The unit featuring the contrapuntal motive comprises only four measures and incorporates a cadence, so that we designate the close in m. 307 to be already the second close. M. 308 brings the same motive back in a triplet variant in the piano. In m. 312 there is again a close, thus the third one.

mm. 313[-26]

This

measure is the actual beginning of the coda, by which the parallelism between

the initial construction (mm. 1–2) and then the beginning of the recapitulation

(m. 198) is demonstrated. Final presentation of the principal theme

[appears] in the basses (piano

and cello); the expunging of all trace of staccato

[leaves only] agonized legato; the counterpoint floats over the theme, as in

the closing theme, by which means the coda remains imbued with the character of

the closing theme.

{8}

Second Movement: Scherzo

Scherzo and Trio: Scherzo as far as m. 71 – The Trio, separated neither by key signature nor by double bar line or title, mm. 72–114. After this, a transition, mm. 115–154, and repeat of the Scherzo mm. 155[–234]. Introduction[:]

mm. 1–4 announces the motives, and right from

the outset with all their various facets, thus: mm. 5–7 with upbeat, we see their facets in fullest operation: first their three-notedness, and the upward motion in 10

mm. 6–16 m. 9 on VII, the mixture and introduction of the third, Dę, which however in the interests of the diatony must eventually

be removed. As a consequence of the Dę, which strays too far

from the diatony, are Aę in m. 11, Dę in

m. 12, at which point the enharmonic change (Dę = Cě) takes effect, and a leap of a fifth is executed: Cě – Fě, in m. 13.

11

The enharmonic change would have had, thus, to be taken as a means of

somehow making good the violent departure from the diatony

⇧ and the lack of respect

for tonality. The duration of this root amounts, just like that of

the two preceding measures, to two measures. Now it moves with each of the two

beats per measure in mm. 15 and 16, in fifths: D – G –

Eę – Aę

.

12

By means of the enharmonic change

and these latter roots, the impact of the VII

ę3 is overcome

⇧ and the modulation completed, and

we find ourselves, at least from D onwards, in the

⇧ new diatony

⇧ of G

minor.

13

The

following music example may illustrate the progress of the [interval of a] second in the melody, and the

way it was made directly possible by this structural harmonic progression

[mm.

11–16]: In m. 17 the I ⇧ Ě3 appears, introduced by its VII, in m. 18 the VII, likewise introduced by its VII (as its neighbor-note harmony) and not until in ⇧ in mm. 19–20 the modulation through ⇧ the steps of a third: F-Aę-C to D-Fě-A 14 is complete, ⇧ whereupon the last cadence ensues. Admittedly the force of this modulation was enhanced in that the preceding structural harmonic progression moves by roots, which were able to suggest a modulation so much earlier. [square-bracketed (by JK):] By the way, for both presumptions, more cogent reasons exist equally well. M. 12 and likewise mm. 14–15 have anticipations on their final eighth notes, on which the bass takes the opportunity to leap up an octave. This anticipation coupled with its octave leap sets the pattern for the bass progression {9} from m. 17 on, which then increases with still greater rhythmic density. In the treble in mm. 17ff it is worth noting the pleasing effect produced in m. 19 by the displacement of the interval of a third in the melody Eę – Cě, which shifts into the second half of the measure, whereas up to then it had occupied the first half of the measure. In

m. 21 the octave leap in the left hand becomes

a leap of a fourth, which promptly continues

with explosive force

four times [recte

twice]

in an imitative manner. Moreover, this motive, as we shall see

later, takes on significance. mm. 23–33 a sort of confirmation, which the new key carries on with a brief independent unit. It was a Brahms speciality to set up a compact entity of this sort on the plateau of the dominant keys, but without in any way thereby committing himself to supplying a middle section to the three-part song form. The rhythmic construction of this compact phrase-unit is not unoriginal: m. 27 mixture, m. 30 shortening to merely three measures, the rhythmic procedure recalling that of Schubert. 16

mm. 35[–43]

The

iteration drives the upward surge until m. 43; but this time the composer moves

from VII to III [mm. 37–38],

which he sets in minor, E[ę]–Gę–Bę. This Gę, which, as in m. 9, was sooner or later surely bound to

descend, offers here the opportunity for enharmonic change Gę

= Fě

[mm. 39–40], and with these

roots, BĚ – EĚ – C – F, adjusted through the

enharmonic {10} change, he succeeds in returning to the diatony. The

progression by steps of a second here is as follows: Thus finally he is able at m. 44 to embark on the downward motion and set up the cadence: in m. 45 the first approach to the dominant is via ę II; in mm. 46, 47 the second approach is via IV–V; after these two approaches, the third is more intricate, and already leads to the close. In mm. 48–49 the structural harmonies Aę – Eę – Bę – F (note how the exit-point occurs a third higher: Dę in m. 44, F in m. 46, Aę in m. 48, these points, in themselves ⇧ understood chromatically, already resulting in the ę III). Now in mm. 50–53 ę II is expansively presented. In mm. 54–61 the cadential motive itself [emerges]. It sounds like an extension of the motive from mm. 17ff (except that the fourth there [becomes] the fifth here). In m. 55 I, in m. 56 IV, in m. 57 VII, in m. 58 passing harmonies to V in m. 59 (cf. the same structural harmonic progression in mm. 17–20), via two chromatic alterations, which point to the neighbor-note harmony of IV [m. 59, beat 2], to IV in m. 60 and the dominant in m. 61, in m. 62 the tonic as the close. The neighbor-note harmony of ę II is overlaid on the tonic; the motive is the fourth-motive from m. 21. It is interesting that this very cadential formation is initially dispensed in three blows, whereas it is extended by immediate repetition to four blows. 17 This happens by virtue of the participation of the viola, which beneath the harmony of [ ę ]II plays a root a third lower: BĚ. 18 The tonic has the major third, cf vol. I. 19

{11}

Trio. in F major,*)

20

begins directly with the dominant;

the structural harmonic progression shows that Brahms did this intentionally, to

close the antecedent on IV in order to be able to reach the connective IV–V at

the beginning of the consequent. A rarely found construction, cf. the master’s

Fourth Symphony, Scherzo, second theme. The structural harmonic progression in

the antecedent is as follows: In mm. 82–83 and in the parallel mm. 84–85, 21 it is worth noting the construction of the eighth-note counterpoint: most particularly, that in mm. 83 and 85 respectively it is on the second eighth note (the notes D and Bę, respectively), and not, as in m. 82 and m. 84, on the fourth, that there are grounds for supposing a change of harmony. m. 84 may be represented as follows: [diagram or music example, not entered]

Consequent:

From this emerges a close on to the tonic from III, falling III to I. The dominant, though not brought into play here, sounds over the tonic in

mm. 107–114 at the same time setting up the

return [to the

Scherzo].

{12}

Movement 3

A1: antecedent: mm. 1–8, consequent: mm. 9–16. m. 1. I–IV5/Ě3, but not II6/5, thus Fě merely a passing tone. m. 4 Suspension 7–6, Gě–Fě m. 5 Accented passing tone E on the third quarter. 22 mm. 11[-16] Organ-point on I Ě7, thus I – IV – ě IV – I [centrally under this expression is "I" linked by horizontal curly bracket.] m. 17 Reiteration, not a consequent phrase, which however, closes in m. 26 not with the tonic but with the dominant in the manner of a consequent, in order to be able to lead better to the second component theme. 23

mm. 19[–20]

mm. 20–22 IV with its subdominant, which is

explained as follows by the passing-motion: On the third and fourth quarter-beats of m. 22,

ě

IV. In m. 20 there occurs twice a

[two-note] fragment of the

motive segment that appears straight afterward in m. 21 (cf. m. 5). The

duplication in m. 20 is also the cause of the duplication in m.

21.

mm. 23[–26]

Arrival

of V and the cadence. The cadence motive, identical to that in m. 7, passes to

the cello in m. 24, to the piano (left hand) in m. 25 {13} and back

to the violin in m. 26. mm. 27–29 The second component theme, destined to bring about modulation, is introduced with the tonic in E major. In m. 30 VI of E major is reinterpreted as II of B major. V of B major arrives as early as m. 31. In m. 32 parallel fifths 7/3 6/2 5/1 occur in the piano. m. 35 B1 in B major; made up of two distinctly different characters juxtaposed; the type can be seen in mm. 35–36 and mm. 37ff. The first segment of the theme lasts for four measures, mm. 35–38, and moves through VI and II in m. 38 to the dominant, with which the second segment opens, in order to close again on the dominant in m. 45 by way of II ě3 in m. 43. mm. 46[–55] Consequent of the second theme with extensions, see m. 47. Instead of mm. 37–38 here in the consequent a reiteration of mm. 35–36 = 46–48. The situation in m. 52 is like that of m. 39. m. 56 to the cadence; its layout suggests at first a cadence in B major, while the piano now introduces a second iteration of the theme, but the progression in mm. 59–61 indicates a modulation back to E major: in m. 59 VI–II, in m. 60 VII–III, in m. 61 I, which is reinterpreted as V of E major, so that at the same place a tonic in E major is sounded in the second half of the measure. mm. 62[–78] Transition to A2; the motive from the second theme extends as far as m. 69. In m. 70 the motive from m. 1 appears in the cello as the first announcement of A2; the second follows in m. 75. The relationship among the keys of these announcements is especially remarkable: C major/minor [in m. 70] – Aę major/minor [in m. 75] – E major/minor in m. 78. If we bear in mind that, prior to C major in m. 70, E major already prevailed, then we can identify the succession of the three keys separated from one another by major thirds, E – C – Aę(Gě) – E, {14} as the cause of the euphony of the E major tonality at the beginning of A2. mm. 78[–110] A2; melody in the piano. The changes are clear to see. m. 111 B2 reduced. mm. 117[‒22] to the subdominant, dominant cadence in m. 118, plagal cadences in mm. 119–120.

© Translation Ian Bent and William Drabkin, 2021 |

|

[in left

margin:]

⇧

Kl. Bibl.

†

Brahms Clavier Quartett Cmoll op. 60

⇧ 1. Ged. Vorders. u. Nachs. Daran schließt sich die

Modulationsgedanke an, mit dem Kopf noch in Cmoll, dann aber nach Es modulierend. 2. Ged. in Es mit einer bei

Brahms ungewöhnlichen Konstruktion: 5-malige Wiederholung, wobei man am besten

dem Gegensatz der Achtel- u. Triolenbegleitung gruppiren möchte: 2 : 3

Wiederholungen, in welchem Sinne dann die ersten beiden gleichsam den

Vordersatz, die letzten 3 den Nachsatz bilden. 3. Ged. T. 110–121 kommt auf den

1. Ged. zurück, der mit dem Motiv aus T. 38 kontrapunktirt wird. Durchführung T.

122–197; Reprise T. 198–Schluß!

1

T. 5 hat im Grunde zur Nachfolge T. 8–9; in den T. 6–7 wird der Ton c gewissermaßen zerdehnt, daher das �� ��. T. 9 Bei der Dominante fehlt die Terz h. T. 17ff Quintfälle: b – es – as – des – ges – c – f; die Melodie eine fallende Sekundreihe in Vergrößerung. T. 21 Dominante, wobei von der Quint chromatisch zur Terz gefallen wird, aber auch die Baß eine der Stimmführung entsprechende Bewegung von g, dem Grundton, wieder zur g zurück über ges–f u. zurück fis–g macht. eine groß auskomponirte Retardation des Sekund-Motivs. ⇧ ? T. 27ff In die Dominanten Harmonie spielen Br. Violine drastisch u. mit Absicht – man beachte p marcato – den unharmonischen u. undiatonischen Ton: e hinein; 2 es klingt beinahe wie Absicht u. Bosheit oder mindestens, wie wenn – um es ganz populär zu sagen – uns jemand an der Nase kitzeln würde, aber schon in T. 30 wird die Bedeutung des Tones dahin klargestellt, daß er als freier Vorhalt zur Sept der Harmonie gebraucht wird. Die Beziehung zur Sept drückt der legato-Bogen beim Klavier aus u. auf dynamischem Gebiete parallel die Wirkung anstrebend das �� -Zeichen: also, das fremde e wird von hier aus nachträglich rehabilitirt. T. 32 Nachsatz; Motiv im staccatto, Orgelpunkt auf c (siehe Vcl.) 3

{2}

Motiv T. 34 Figurirung des T. 5,

somit T. 38 Motiv bei Vcl. u. Br. Verkleinerung des Motivs beim Klavier T. 37.

T. 42ff Motiv beim Klavier abwechselnd bei der

r. u. l. Hand; Sechzehntel-Kontrapunkt neu: ⇧ freilich T. 45 Eigentlicher Sitz der Modulation Cm nach Gm. T. 49 Modulation nach Esdur/moll; interessant beim 16tel Kontrapunkt die allmälige Verringung des Quartintervalles, das zum 1. mal in T. 44 zwischen dem letzten 16tel des 2. u. dem 1. des 3. Viertels sich öffnet. Im T. 48 wird aus der Quart eine Terz, T. 49 ein Sekundschritt: b – a.

T. 50 Das Brio des 16tel sich zum legato gelegt, nun

darf es im legato auch tranquillo werden.

4

[cue sign to

verso]

T. 72+73 sind im Grunde so zu sehen: [left blank] T. 74 Oktaven zwischen Sopran u. Baß, nicht nur wegen der Stufen, sondern auch wegen des dazwischentretenden Quartschrittes gut. T. 77 Dominante schließt die 8-taktige Tonreihe, so daß die nachfolgende Wiederholung zunächst als Nachsatz gehört wird. T. 78ff Variation der Melodie bei der Violine, wieder zur Dominante in T. 85. Man beachte die Verschiedenheit der Baßführung in T. 78–81 gegenüber der die T. 70–73. T. 86 Triolen-Begleitung Vl. u. Br.; Vcl. figurirt die Tonreihe des T. 70, worauf das Klavier im Thema fortfährt. T. 88 Beim Vcl. Verschleierung des Sachverhaltes durch Wiederholung des Motivs aus T. 86; man neigt infolgedessen in T. 86 die Bedeutung der Figur zu verkennen. Gerade eine solche Versch[l]eierung aber ist ech[t] symphonisch! {3} In T. 91 wieder Halbschluß, zum 3. male. T. 94 Wiederholung der T. 86ff, ebenso wie früher T. 77ff Wiederholung der T. 70ff gewesen. Mischung Esm. T. 100 Nicht mehr zur Dominante geht es, sondern eine kräftige Kadenz führt zur letzten 5. Wiederholung des Themas, die mit g, also eine Terz höher beginnt. T. 122 Beginn der Durchführung, 1. Motiv im Portamento; aber dieses Portamento erweist sich als der Uebergang vom legato zum staccatto im T. 142. T. 130 deutlich Esm. T. 138 vgl. T. 50 T. 142ff Plan: 5 Einem geschlossenen Bildchen in Hd, T. 142–151, bezw. 152 tritt eine modulatorisch suchende Partie von T. 154–163 gegenüber; nun wieder, aber in Gd, ein geschlossenes Bildchen, T. 164–174, dem wieder suchend u. modulierend eine Partie von T. 176 bis Ende der Durchführung gegenüber tritt; vgl. IX. Sinf. 6 T. 152–153 Ueberleitung vom geschlossenen Bild zum Gegenbild. T. 154 Beim jeweilig 3. Viertel Vorausnahme der Harmonie des jeweilig nachfolgenden 1. Viertels nach Art einer Synkope. In T. 156–159 beachte man als Grundtöne, (nicht als Stufen!) die Terz-Schritte d – b – dis – h. T. 161 Hemiolenartige Verdichtung; Harmonie: [music example probably intended but not entered] T. 176 Nach der Durchführung des Motivs des 1. Themas folgt hier eine des 2. Themas auf dem Orgelpunkt G u. kanonisch ausgeführt; die imitirende Stimme setzt zuerst im Abstand von 3 Vierteln, also eines ganzen Taktes ein, siehe T. 177–178, in T. 185 setzt, sie bereits nach 2 Vierteln ein, während sie endlich in T. 191 bereits nach einem Viertel einsetzt; hier tritt noch eine {4} 2. Stimme, siehe Klavier, imitierend ein. Harmonien!

Reprise

T. 236 2. Ged. in Gd statt in Cd, ungeheure Verbreiterung der Gdur Tonart: hier im Gegensatz zum 1. Teil 6x8 statt 5x8. 7 Die gewissermaßen überzähligen 8 Takte sind die T. 244–251; sie dienen nicht so sehr als wirkliche Wiederholung, sondern als Erzeugungsstätte des Baßmotivs der T. 252ff. Man beachte folgende, durch die Harmonien begründete Veränderungen des Intervalls: [music example, not entered] Ist so auch diese 8-taktige Gruppe mehr als Ueberleitungsgruppe erkannt worden, so müssen dann erst die Takte T. 252–259 als die wahre 1. Wiederholung gelten; treu dem Thema in den ersten vier Takten wird sie freier in den nachfolgenden 4 Takten, nur daß sie den Zug zur Dominante beibehält. Diese Wiederholungen nun werden – u. dieses macht die wirkliche Verbreiterung aus – noch einmal in Moll, kraft der Mischung, gebracht. T. 254 Scheinbar offene Quinten; in Wahrheit ein zufälliges Zusammentreffen zwischen der Nebennote des Basses cis u. dem Durchgang g des Soprans; man braucht also nur die Nebennote im Baß zu streichen, um sich zu überzeugen, daß keine Quinten-Fortschreitung vorliegt! {5} T. 260–269 Dehnung zu 10 Takten; nun erst die Triolenbegleitung, vgl. im 1. Teil T. 86, die den Nachsatz anzeigt. Dieser enthält wieder 2 Wiederholungen: die zweite T. 278 muß nun von T. 282 die Modulation nach der eigentlichen Tonart Cd bringen. Beethoven pflegte in solchen Fällen, d.h. wo er gleichsam unfreiwillig auf ein falsches Geleise geriet – s.z. B. Sonate Esd, op. 7, Rondo ,: Esd – Ed – Esd; Sonate op. 110, 1. S.: Asd – Desd – Cism – Ed – Asd 8 – schon früher in die Hauptonart einzulenken, mit einer Gebärde gleichsam, als würde er für die Entgleisung um Entschuldigung bitten u. als würde er sagen wollen, daß er sich gerade noch rechtzeitig erinnere, welchen Weg er eigentlich zu gehen habe. Hier bei Brahms steht die Sache etwas schlimmer: so richtig das beiläufige Hineinrutschen nach Gd als beiläufig dargestellt wird, so wenig richtig ist es, daß er Gd so lange ausführlich behält, so daß es für ihn zu spät wird um zu sagen: pardon, ich bin auf falschem Wege. Wäre es doch auch grottesk, wenn jemand, der an einem Tisch sitzt, an den er nicht gehört, dieses erst bemerken wollte, nachdem er die volle Mahlzeit genossen. Die Modulation bei Brahms ist daher ein notwendiges Uebel; sie klingt auch motivisch verlegen u. unwahr. Es ist sonst nicht Brahms Art, ohne weitere Uebergänge von Motiven, wie die in T. 279– 200 [recte 280] , zu solchen zu gelangen, die T. 282–283 zeigen. Aber freilich, er wollte zwei Fliegen mit einem Schlage treffen: die Figur des T. 283 soll nämlich noch außerdem den Vorfahren der Triolenfigur in T. 289ff vorstellen. Die Figur bleibt banal. Der Accord in T. 287 ist alterirt: Terz-Quart-Accord u. wird hier in der Bedeutung von V in C u. nicht II in Fm, benützt. {6} Bei T. 288 Schlußgedanke. Diesmal lastet auf ihm anders als im 1. Teil, die Verpflichtung die Haupttonart Cd nach der vorausgegangenen breiten Darstellung des Gd zur nachdrücklichen Selbstbehauptung u. zum Triumphe zu führen. Die Aufriß der

T. 288–300 lautet wie folgt: [diagram or music

example, not entered]

T. 30 50–30 83 bleibt. Die Kadenz selbst, T. 300–303, beschreitet den usuellen Stufengang: [diagram or music example, not entered] Die große Aktualität u. die intensive Durcharbeitung des Sekundmotivs läßt es uns zunächst gar nicht merken, daß der Kontrapunkt, wie ihn der 3. Gedanke im 1. Teil bei der Vl., später Vcl., s. T. 110–111, bezw. T. 114–115 bringt, entfallen ist. Dieser Kontrapunkt wird nun eben in T. 304–312 nachträglich u. zu einem selbstständigen Gebilde verarbeitet. So wurde der Schlußgedanke des 1. Teiles zuerst {7} in bezug auf das Hauptmotiv u. sodann in bezug auf dessen Kontrapunkt in 2 Teilen ausgeführt. Erst hier die Haupttonart Cm statt Cd. Das aus dem Kontrapunktmotiv gewonnene Bildchen zählt nur 4 Takte u. legt in sich wieder einen Kadenzweg zurück, so daß wir den Schluß in T. 307 bereits als den 2. Schluß bezeichnen. T. 308 bringt dasselbe Motiv in Triolen-Variation beim Klavier. In T. 312 wieder Schluß, somit bereits der dritte.

T. 313 Eigentlich mit diesem Takt Beginn der

Coda, wodurch der Parallelismus der Anfangskonstruktion T. 1–2, sodann zum

Beginn der Reprise, T. 198, gegeben ist. Letzte Darstellung des Hauptthemas bei

den Bässen, Klavier u. Vcl.; die Ueberwindung alles Staccattomäßigen –

schmerzliches legato; der Kontrapunkt steht über dem Thema, wie beim

Schlußgedanken, wodurch der Coda wieder der Schlußgedanken-Charakter aufgeprägt

bleibt.

{8}

II. Satz: Scherzo

Scherzo mit ; Scherzo bis T. 71 – weder durch Vorzeichen noch durch Doppelstriche oder Titel gesondert von T[.] 72–114, hierauf Ueberleitung von T. 115–154, von T. 155 Wiederholung des Scherzo. Einleitung[:]

T. 1–4 kündigt die Motive an u. sofort auch

schon mit allen Elementen der Mannigfaltigkeit, so T. 5ff mit Auftakt, sehen wir die Elemente in vollster Tätigkeit: zunächst die 3-Tönigkeit u. die Bewegung aufwärts in 10

T.

56–16. T. 9 auf der VII Stufe die Mischung u. Einführung der Terz „des“, die aber

im Interesse der Diatonie doch wieder weggebracht wird. Als Konsequenz des

„des“, das von der Diatonie zu weit wegführt, sind „as“ in T. 11, „des“ in T.

12, wo die Enharmonie einsetzt (des=cis), u. ein Quintschritt vollzogen wird:

cis–fis, T. 13.

11

Die Enharmonie mußte also zuhilfe genommen werden um den starken Bruch gegenüber

der Diatonie

⇧ u. den

Mangel an Ton-[?Kultus]

irgendwie gut zu machen. Die Dauer dieses Grundtones beträgt, ebenso wie die der

beiden vorhergehenden, 2 Takte. Nun geht es mit je 2 Schlägen in T. 15 u. 16 in

Quinten: d – g – es – as.

12

Durch die Enharmonie u. die letzgenannten

Grundtöne ist der Einschlag der VII

ę3 Stufe überwunden

⇧ u. zugleich die Mod. vollzogen u.

wir befinden uns mindestens von d ab in der

⇧ neuen Diatonie

⇧ gm.

13

Den Fortgang der Sekund in der Melodie, wie er gerade

durch diesen Stufengang ermöglicht wurde, mag folgendes Bild

veranschaulichen: T. 17 erscheint die I ⇧ Ě3 von ihrer VII. präludiert, in T. 18 die VII, ebenfalls von ihrer VII. präludiert (als ihrer Nebennotenharmonie) u. erst in den ⇧ in den T. 19–20 ⇧ wird die Modulation durch ⇧ der ⇧ Terz-Schritte: f–as–c zu d–fis–a 14 vollzogen, ⇧ worauf die letzte Kadenz einsetzt[.] ⇧ Freilich wurde die Eindruck dieser Modulation dadurch gefördert, daß die vorausgegangene Stufengang sich in Grundtönen bewegte, die eine Modulation sogar schon früher nahelegen konnten. [square-bracketed (by JK):] Für die beiden Annahmen liegen übrigens gleich triftiger Gründe vor. T. 12, desgleichen T. 14–15 weisen Antizipationen beim letzten Achtel auf, bei welcher Gelegenheit der Baß einen Oktavsprung macht[.] Diese Antizipation samt Oktavsprung ist Vorbild der Baßführ- {9} -ung von T. 17 an, die sich zu einem noch dichteren Rhythmus steigert. Bei dem Sopran in den T. 17ff beachte man die wohltuende Wirkung, die in T. 19 die Umstellung des Terzintervalles der Melodie es–cis hervorbringt, das in die 2. Hälfte des Taktes gerät, während es bis dahin die 1. Hälfte des Taktes occupiert hatte. In

T. 21 wird aus dem Oktavsprung des l.H. ein

Quart-Intervall, das sich sofort mit

explosiver Wirkung auf imitierendem Wege 4mal fortsetzt. Auch dieses Motiv

erhält, wie wir später sehen werden, Bedeutung. T. 23–33 eine Art Bestätigung, die die neue Tonart durch ein kleines selbständiges Bildchen erhält. Ein Brahms’sches Spezifikum, auf dem Plateau der Dominanten-Tonarten ähnliche kleine Gebilde aufzustellen, ohne damit aber etwa die Absicht zu verbinden, ein Mittelstück der 3-teiligen Liedform zu geben. Nicht unoriginell ist die rhythmische Konstruktion des kleinen Sätzchens: T. 27 Mischung, T. 30 Abkürzung zu blos 3 Takten, die Rhythmik erinnert an die Schubertsche. 16

T. 35ff Die Wiederholung betreibt die

Aufwärtsrichtung bis T. 43; von der VII. Stufe wendet sich hier aber der Autor

zur III., die er in Moll setzt: e–ges–b. Dieses ges, das, ebenso wie in T. 9,

doch früher oder später fallen mußte, gibt hier Veranlassung zur Enharmonie: ges

= fis u. bei diesen, der enharmonischen {10} Umwechslung angepassten

Grundtönen h – e – c – f erobert er wieder die Diatonie. Die Sekundfortgang

lautet hier: So kann er endlich bei T. 44 die Abwärtsrichtung in Angriff nehmen u. die Kadenz in Scene setzten: in T. 45 der 1. Anlauf zur Dominante über die erniedrigte II.; in T. 46, 47 der 2. Anlauf über IV–V; nach diesen 2 kurzen Anläufen der dritte umständlichere, der bereits zum Schluß führt. In den T. 48–49 die Stufen as – es – Bb – f (man beachte, wie der Ausgangspunkt um eine Terz höher fällt: des in T. 44, f in T. 46, as in T. 48, welche Punkte in sich ⇧ chr. Sinnung schon die ę III. Stufe der Tonart ergeben). Nun in T. 50–53 die ę II. Stufe breit exponiert. In T. 54–61 das Kadenz-Motiv selbst. Es klingt wie eine Erweiterung des Motivs in T. 17ff (statt der Quart dort ⇧ der Quint hier). In T. 55 die I. Stufe, in T. 56 die IV, in T. 57 die VII. in T. 58 Durchgang zur V. in T. 59; vergleiche denselben Stufengang in den T. 17–20. Ueber 2 Chromen, die auf die Nebennoten-Harmonie der IV. hinweisen zur IV. in T. 60–61 u. in T. 61 die Dominante, in T. 62 die Tonika als Schluß. Auf die Tonika die Nebennoten-Harmonie der ę II.; das Motiv ist das Quartmotiv aus T. 21. Interessant ist, daß eben dieses Cadenzerscheinung zunächst in 3 Schlägen erledigt wird, während sie bei der sofortigen Wiederholung zu 4 Schlägen erweitert wird! 17 Dieses geschieht durch die Beteiligung der Bratsche, die unter die Harmonie der II. Stufe eine um eine Terz tieferliegenden Grundton: h setzt. 18 Die Tonika hat die Dur-Terz, vgl. Band I. 19

{11}

Trio. in Fdur,

20

fängt somit mit der Dominante an, der

Stufengang erweist, daß Brahms darauf bedacht war; den V.S. mit der IV.

abzuschließen, um den Anschluß: IV–V zu Beginn des Nachsatzes erreichen zu

können. Eine seltene Konstruktion, vgl. des Meisters IV.

Sinfonie, Scherzo, II. Ged. Der Stufengang ist im Vordersatz

folgender: Man beachte in T. 82–83 u. in den parallelen T. 84–85 21 die Konstruktion des Achtel-Kontrapunktes: eben der Umstand, daß in T. 83, bezw. T. 85, schon das 2. Achtel, u. nicht wie in T. 82 bezw. T. 84 das 4. de nr Ton „d“ bezw. „b“ ist, ist dafür maßgebend, einen Wechsel der Harmonie anzunehmen. Das Bild von T. 84 stellt sich wie folgt: [diagram or music example, not entered]

Nachsatz: Daraus ergibt sich ein Schluß zur Tonika von der III. Stufe fallend: III–I. Die nicht in Verwendung gebrachte Dominante klingt aber über der Tonika in den

T. 107–114 fort, zugleich die Rückleitung

vorbereitend.

{12}

III. Satz

A1: Vordersatz: T. 1–8, Nachsatz: T. 9–16. T. 1. Stufen: I–IV5/Ě3, nicht aber II6/5, also fis blos Durchgang. T. 4 Vorhalt 7 6, gis–fis T. 5 Beim 3. Viertel Wechselnote e. 22 T. 11 Orgelpunkt auf I Ě7, also I – IV – ě IV – I [centrally under this expression is "I" linked by horizontal curly bracket.] T. 17 Wiederholung, nicht Nachsatz, die aber nicht mit der Tonika, sondern mit der Dominante, in T. 26 schließt nach Art eines V.S., um zum 2. Teilgedanken 23 besser hierüberführen zu können.

T. 19ff

T. 20–22 Die IV. Stufe mit ihrer

Unterdominante, die sich wie folgt aus dem Durchgang erklärt: Beim 3. u. 4. Viertel des T. 22

ě

IV. Stufe. In T. 20 wird zweimal gesetzt, ein

Element des sofort im T. 21 auftretenden Teilmotivs vgl. T. 5. Die Duplizität in

T. 20 ist auch Ursache der Duplizität in T. 21.

T. 23ff Eintritt der V. Stufe u. Kadenz. Das

Kadenz-Motiv, dasselbe wie in T. 7, passiert in T. 24 das Cello, in T. 25 das

Klavier (l.H.) {13} u. kehrt in T. 26 wieder zur Violin

zurück. T. 27ff II. Teilgedanke, der auch die Modulation bringen soll, wird eröffnet mit der Tonika in Ed. T. 30 findet die Modulation Umdeutung der VI. aus Ed in eine II. aus Hd statt. In T. 31 bereits die V. von Hd. In T. 32 beim Klavier offene Quinten 7/3 6/2 5/1. T. 35 B1 in Hd; aus 2 verschiedenen Charakteren zusammengestellt; man siehe den Typus in T. 35–36 u. in T. 37ff. Der 1. Teil des Ged. zählt 4 Takte, T. 35–38 u. wendet sich über die VI. u. II. Stufe in T. 38 zur Dominante, mit der der II. Teil eröffnet wird, um über die II ě3 in T. 43 auch wieder mit der Dominante in T. 45 zu schließen. T. 46ff Nachsatz des II. Ged. mit Dehnungen, siehe T. 47. Statt der T. 37–38 hier im Nachsatz eine Wiederholung der T. 35–36 = 46–48. Bei T. 52 die Situation wie bei T. 39. T. 56 Zur Kadenz; die Anlage derselben weist zunächst auf eine Kadenz in Hd hin, während das Klavier eine nunmehr 2. Wiederholung des Gedankens bringt, aber der Stufengang in den T. 59–61 zeigt eine Rückmodulation nach Ed: in T. 59: VI–II, in T. 60: VII–III, in T. 61: I., die in eine V. in Ed umgedeutet wird, so daß daselbst in der 2. Hälfte des Taktes eine Tonika aus Ed erklingt. T. 62ff Ueberleitung zu A2; Motiv aus dem 2. Ged. bis T. 69; in T. 70 klingt beim Cello das Motiv des T. 1 als 1. Ankündigung des A2; die zweite erfolgt in T. 75. Die Beziehung, in der die Tonarten der Ankündigungen stehen, ist besonders bemerkenswert : Cdur/moll – Asdur/moll – Edur/moll in T. 78. Erwägt man, daß vor Cd in T. 70 bis dahin bereits Ed herrschte, so weiß man in dem Ablauf der 3 in Entfernung von großen Terzen liegenden Tonarten: E – C – As(Gis) – E die Ursache für den Wohlklang der Ed-Tonart bei Beginn von A2 {14} anzuegeben. T. 78 A2; Melodie beim Klavier. Die Veränderungen liegen klar zu Tage. T. 111 B2 reduziert.

T. 117 zur Unterdominante, Dominanten Schluß in

T. 118, 119–120 plagale Schlüsse.

© Transcription Ian Bent, 2021 |

|

[in left

margin:]

⇧

Little

Library

†

: Brahms Piano

Quartet in C minor, Op. 60

⇧ First theme, antecedent and consequent. Contiguous

to that is the modulatory theme, at the outset still in C minor, but then

modulating to Eę. Second theme in Eę with

a construction uncommon in Brahms’s works: fivefold iteration, which might best

be grouped by the contrast between eighth note and triplet accompaniment: 2 + 3

iterations, the first two accordingly forming, as it were, the antecedent, the

latter three the consequent. Third theme, mm. 110–21, reinvokes the first theme,

which is set in counterpoint with the motive from m. 38. Development section mm.

122–97; recapitulation mm. 198–end!

1

m. 5 is in principle continued by mm. 8–9; in mm. 6–7 the note C is somewhat extended, hence the �� ��. m. 9 The third, BĚ, is absent from the dominant. mm. 17[-20] Succession of descending fifths: Bę – Eę – Aę – Dę – Gę – C – F; the melody an expanded succession of descending seconds. mm. 21[-27] Dominant, in which occurs a chromatic descent from the fifth to the third, and in addition the bass line describes a motion, in accordance with the voice-leading, from G, the bass note, back to G, passing through Gę to F and back again via Fě to G – an expansively composed-out retardation of the motive of a second. ⇧ ? mm. 27-29 Into the dominant harmony the viola and violin inject abruptly and with intent – NB the p marcato – the non-harmonic and non-diatonic tone E; 2 it sounds almost as if done deliberately and with malice, or at least as if – to put it in popular terms – someone were to tickle our nose, but already in m. 30 the significance of that tone is explained: it serves as a free [upward] suspension to the seventh of the harmony. Its relationship to the seventh is expressed by the legato slur in the piano part, and parallel with that in the dynamic sphere by the crescendo sign, which strives for the same effect at the dynamic level: thus, the foreign E is rehabilitated after the event. m. 32 Antecedent; motive [now played] staccato, [with] organ-point C (see cello). 3

{2}

Motive m. 34 Figuration from m. 5,

thus: m. 38 Motive in the cello and viola [is a] diminution of the motive in the piano at m. 37.

mm. 4

2 [recte

3]

[-49]

Motive in the piano

alternating between right and left hands; sixteenth-note counterpoint new:

⇧ thus m. 45 True site of the modulation from C minor toward G minor. m. 49 Modulation toward Eę major/minor; interesting in the sixteenth-note counterpoint [is] the gradual narrowing of the interval of a fourth, which opens up for the first time in m. 44, between the last sixteenth of the second quarter note beat and the first of the third. In m. 48 the fourth becomes a third, in m. 49 a second: Bę–A.

m. 50 The brightness of the sixteenth

note[s] settles down to a legato, now in legato it can also become tranquillo.

4

[cue sign to

verso]

mm. 72-73 In essence, they are: [left blank] m. 74 Parallel octaves between treble and bass are good, not only by virtue of the structural harmonies, but also by virtue of the intervening leap of a fourth. m. 77 The dominant closes the 8-measure melodic line, so that the succeeding iteration is now heard as a consequent. mm. 78[-85] Variation of the melody in the violin, [leading] again to the dominant in m. 85. Note the difference in the bass line in mm. 78–81 as against that of mm. 70–73. m. 86 Triplet accompaniment in violin and viola; cello creates a figure out of the note-pattern at m. 70, whereupon the piano carries the theme forward. m. 88 The repetition of the m. 86 motive in the cello causes a veiling of the situation; as a result, one is inclined not to recognize the significance of the figure in m. 86. But such a veiling is genuinely symphonic! {3} In m. 91 again a half-cadence, for the third time. m. 94 Reiteration of mm. 86[–93], just as earlier mm. 77 [recte 78] [–85] were a reiteration of mm. 70[–77]. Mixture Eę minor. m. 100 It no longer goes to the dominant; instead a powerful cadence leads to the fifth and final iteration of the theme, which begins with the note G, thus a third higher. m. 122 Beginning of the development section, motive 1 in portamento; but this portamento proves to be the transition from legato to the staccato in m. 142. m. 130 clearly Eę minor. mm. 138[-40] Cf. mm. 50[–52]. mm. 142[-97] Plan 5 : A closed unit in B major, mm. 142–151(152), is now confronted by a passage, mm. 154–163, which seeks to make a modulation; and then again, but now in G major, a closed unit, mm. 164–174, is confronted by a passage, mm. 176 to the end of the development section, which again seeks to make a modulation; cf. Ninth Symphony . 6 mm. 152–153 Transition from the closed unit to the contrasting section. m. 154 On the third quarter note beat of each measure, the anticipation of the harmony on the first quarter note beat of the following measure [creates] a sort of syncope. In mm. 156–59 NB as bass notes (not as structural harmonies!), the steps of a third: D – Bę – Dě – BĚ. m. 161 Hemiola-like compression; harmony: [ music example probably intended but not entered ] m. 176 After the development of the motive of the first theme, there follows at this point one of the second theme deployed canonically over the organ-point G; the imitative voice enters at first at three quarters’ distance, thus a whole measure apart, see mm. 177–78, then at m. 185 it enters earlier, at two quarters’ distance, while finally at m. 191 it enters still earlier, at one quarter’s distance; at this point there enters a {4} second voice, see the piano part, in imitation. Harmonies!

Recapitulation

m. 236 Second theme in G major instead of C major, massive expansion of the G major key: here, in contrast to the first section, 6 x 8 instead of 5 x 8. 7 The supernumerary eight measures are mm. 244–51; they serve not so much as a genuine iteration, but rather as the source of the bass motive at mm. 252[–66]. Note in what follows the harmonically-based alterations of the interval: [music example, not entered] If then this 8-measure group is also perceived more as a transitional group, then first the measures mm. 252–59 must count as the true first iteration; adhering faithfully to the theme in its first four measures, it [i.e. the group] becomes freer in the following four measures, except that it conserves the motion to the dominant. These iterations are now – and it is they that provide the real expansion – once again brought into the minor key by virtue of mixture. m. 254 What appear to be parallel fifths are in reality an accidental concurrence of the neighbor-note Cě in the bass and the passing tone G in the treble. Thus it is necessary only to excise the neighbor-note in the bass to be convinced that no fifth-progression exists! {5} mm. 260–69 Extension to ten measures; only now [comes] the triplet accompaniment (cf. m. 86 in the exposition), which heralds the consequent. The latter again comprises two iterations: the second, m. 278, must now from m. 282 bring the modulation round to the rightful key of C major. Much earlier, Beethoven in such cases – i.e. where he has strayed almost involuntarily on to a false path, as for example in the Eę major Sonata, Op. 7, Rondo: Eę major – E major – Eę major; Sonata Op. 110, first movement: Aę major – Dę major – Cě minor – E major –Aę major 8 – used to come back to the principal key with a gesture as if he were apologizing for the derailment and wanted to say that he had realized at the last possible moment which path he was actually supposed to take. Here, in Brahms’s music, the matter is somewhat more serious: however justified it may be to present a brief slip into G major as a passing phenomenon, it is less than justified for him to dwell elaborately and for so long in G major, such that it becomes too late for him to say: “Sorry, I’ve taken the wrong path.” It would be downright grotesque if someone who sits at a table to which he doesn’t belong fails to notice the fact until he has finished the meal. Brahms’s modulation is therefore a necessary evil; even motivically, it sounds embarrassed and inauthentic. It is not Brahms’s normal way to arrive at such transformations as are found in mm. 282–83 without further motivic transformation of the sort shown in mm. 279–80. But of course he wanted to kill two birds with one stone. The figure at m. 283 will in fact even prove to be the precursor of the triplet figure in mm. 289ff The figure remains banal. The chord in m. 287 is altered: [it is a] 4/3-chord, and is employed here in the sense of V of C, not II of F minor. {6} At m. 288 cslosing theme. This time, unlike in the exposition, it is charged with the obligation to carry the principal key, C major, after the preceding, expansive presentation of G major, through to emphatic self-reassertion and to triumph. The plan of

mm. 288–300 is as follows: [diagram or music

example, not entered]

mm. 30 50–30 83 The cadence itself (mm. 300–303) follows the conventional structural harmonic progression: [diagram or music example, not entered] The sheer amount of activity and the intensive working out of the second motive distracts us completely from noticing the absence of the counterpoint that the third theme presented in section I in the violin, later cello (mm. 110–11 and 114–15). This counterpoint now in mm. 304–12 [are] developed belatedly and as an independent unit. Thus the closing theme of section I was at first {7} set forth with reference to the principal motive, and subsequently with reference to its counterpoint, in two partitions. Only now here [is] the principal key C minor, instead of C major. The unit featuring the contrapuntal motive comprises only four measures and incorporates a cadence, so that we designate the close in m. 307 to be already the second close. M. 308 brings the same motive back in a triplet variant in the piano. In m. 312 there is again a close, thus the third one.

mm. 313[-26]

This

measure is the actual beginning of the coda, by which the parallelism between

the initial construction (mm. 1–2) and then the beginning of the recapitulation

(m. 198) is demonstrated. Final presentation of the principal theme

[appears] in the basses (piano

and cello); the expunging of all trace of staccato

[leaves only] agonized legato; the counterpoint floats over the theme, as in

the closing theme, by which means the coda remains imbued with the character of

the closing theme.

{8}

Second Movement: Scherzo

Scherzo and Trio: Scherzo as far as m. 71 – The Trio, separated neither by key signature nor by double bar line or title, mm. 72–114. After this, a transition, mm. 115–154, and repeat of the Scherzo mm. 155[–234]. Introduction[:]

mm. 1–4 announces the motives, and right from

the outset with all their various facets, thus: mm. 5–7 with upbeat, we see their facets in fullest operation: first their three-notedness, and the upward motion in 10

mm. 6–16 m. 9 on VII, the mixture and introduction of the third, Dę, which however in the interests of the diatony must eventually

be removed. As a consequence of the Dę, which strays too far

from the diatony, are Aę in m. 11, Dę in

m. 12, at which point the enharmonic change (Dę = Cě) takes effect, and a leap of a fifth is executed: Cě – Fě, in m. 13.

11

The enharmonic change would have had, thus, to be taken as a means of

somehow making good the violent departure from the diatony

⇧ and the lack of respect

for tonality. The duration of this root amounts, just like that of

the two preceding measures, to two measures. Now it moves with each of the two

beats per measure in mm. 15 and 16, in fifths: D – G –

Eę – Aę

.

12

By means of the enharmonic change

and these latter roots, the impact of the VII

ę3 is overcome

⇧ and the modulation completed, and

we find ourselves, at least from D onwards, in the

⇧ new diatony

⇧ of G

minor.

13

The

following music example may illustrate the progress of the [interval of a] second in the melody, and the

way it was made directly possible by this structural harmonic progression

[mm.

11–16]: In m. 17 the I ⇧ Ě3 appears, introduced by its VII, in m. 18 the VII, likewise introduced by its VII (as its neighbor-note harmony) and not until in ⇧ in mm. 19–20 the modulation through ⇧ the steps of a third: F-Aę-C to D-Fě-A 14 is complete, ⇧ whereupon the last cadence ensues. Admittedly the force of this modulation was enhanced in that the preceding structural harmonic progression moves by roots, which were able to suggest a modulation so much earlier. [square-bracketed (by JK):] By the way, for both presumptions, more cogent reasons exist equally well. M. 12 and likewise mm. 14–15 have anticipations on their final eighth notes, on which the bass takes the opportunity to leap up an octave. This anticipation coupled with its octave leap sets the pattern for the bass progression {9} from m. 17 on, which then increases with still greater rhythmic density. In the treble in mm. 17ff it is worth noting the pleasing effect produced in m. 19 by the displacement of the interval of a third in the melody Eę – Cě, which shifts into the second half of the measure, whereas up to then it had occupied the first half of the measure. In

m. 21 the octave leap in the left hand becomes

a leap of a fourth, which promptly continues

with explosive force

four times [recte

twice]

in an imitative manner. Moreover, this motive, as we shall see

later, takes on significance. mm. 23–33 a sort of confirmation, which the new key carries on with a brief independent unit. It was a Brahms speciality to set up a compact entity of this sort on the plateau of the dominant keys, but without in any way thereby committing himself to supplying a middle section to the three-part song form. The rhythmic construction of this compact phrase-unit is not unoriginal: m. 27 mixture, m. 30 shortening to merely three measures, the rhythmic procedure recalling that of Schubert. 16

mm. 35[–43]

The

iteration drives the upward surge until m. 43; but this time the composer moves

from VII to III [mm. 37–38],

which he sets in minor, E[ę]–Gę–Bę. This Gę, which, as in m. 9, was sooner or later surely bound to

descend, offers here the opportunity for enharmonic change Gę

= Fě

[mm. 39–40], and with these

roots, BĚ – EĚ – C – F, adjusted through the

enharmonic {10} change, he succeeds in returning to the diatony. The

progression by steps of a second here is as follows: Thus finally he is able at m. 44 to embark on the downward motion and set up the cadence: in m. 45 the first approach to the dominant is via ę II; in mm. 46, 47 the second approach is via IV–V; after these two approaches, the third is more intricate, and already leads to the close. In mm. 48–49 the structural harmonies Aę – Eę – Bę – F (note how the exit-point occurs a third higher: Dę in m. 44, F in m. 46, Aę in m. 48, these points, in themselves ⇧ understood chromatically, already resulting in the ę III). Now in mm. 50–53 ę II is expansively presented. In mm. 54–61 the cadential motive itself [emerges]. It sounds like an extension of the motive from mm. 17ff (except that the fourth there [becomes] the fifth here). In m. 55 I, in m. 56 IV, in m. 57 VII, in m. 58 passing harmonies to V in m. 59 (cf. the same structural harmonic progression in mm. 17–20), via two chromatic alterations, which point to the neighbor-note harmony of IV [m. 59, beat 2], to IV in m. 60 and the dominant in m. 61, in m. 62 the tonic as the close. The neighbor-note harmony of ę II is overlaid on the tonic; the motive is the fourth-motive from m. 21. It is interesting that this very cadential formation is initially dispensed in three blows, whereas it is extended by immediate repetition to four blows. 17 This happens by virtue of the participation of the viola, which beneath the harmony of [ ę ]II plays a root a third lower: BĚ. 18 The tonic has the major third, cf vol. I. 19

{11}

Trio. in F major,*)

20

begins directly with the dominant;